Generation Z’s voracious appetite for collecting — from blind-box toys and limited-edition sneakers to photocards and vintage comics — reflects more than nostalgic hobbyism; it’s a consumer behavior shaped by deliberate design and psychological levers. This paper explores why collecting has become a distinctive cultural practice for Gen Z by bringing together frameworks from behavioral economics (scarcity, loss aversion, and variable rewards), Gestalt principles of perception (figure/ground, closure, and grouping), and multisensory design (tactile, visual, and auditory cues that heighten perceived value). Contemporary product and experience designers intentionally craft emotional and sensory decision pathways — using affordances, depth cues, and surprise mechanics — that turn ordinary purchases into identity-weighted rituals and status signals. Drawing on class readings and additional scholarly and industry sources, this exploratory study will map how these design strategies interact to create compulsive, community-oriented collecting practices among Gen Z.

At its core, the act of collecting taps into fundamental psychological drives that shape how consumers interact with objects, structure, and identity. Recent research in the Journal of Consumer Research shows that one of the most powerful motivations for collecting is a desire for control, as individuals seek structure and order in their possessions by building coherent sets of related items; the closer a collection is to completion, the stronger the motivational pull toward acquiring additional pieces becomes, because completing the set reinforces a sense of mastery over one’s environment and goals (Cao et al., 2025). The article also identifies multiple psychological drivers of collecting behavior: some individuals collect for identity expression, using items to signal personal history or group belonging, while others derive joy, nostalgia, or pleasure from the pursuit itself. These motives underscore that collecting is more than mere acquisition — it involves emotional reinforcement, cognitive fulfillment, and social meaning, making the act of acquiring and organizing objects deeply intertwined with human psychology.

Getting into behavioral economics, these concepts further amplify these psychological tendencies by shaping the conditions under which Gen Z encounters collectible products. Many contemporary collectibles — from blind boxes to limited sneaker drops — are engineered around scarcity, variable-reward schedules, and anticipatory dopamine cycles, all of which nudge consumers toward repeated purchases. Scarcity operates as a powerful cognitive bias: when an item is framed as rare or part of a finite series, its perceived value increases, and the urgency to act outweighs rational decision-making. Variable rewards, commonly seen in game design and gambling, appear in blind-box culture, where the uncertainty of which item is inside triggers a reward-prediction loop that encourages “just one more” purchase. Loss aversion also plays a role, as consumers fear missing out on a drop or failing to complete a set — a design tactic that pushes them toward quicker, less deliberative choices. As Bridgeable’s design principles highlight, these behavioral levers aren’t accidental; they are strategically embedded in product ecosystems to guide emotional and impulsive decision-making (Bridgeable). In the context of Gen Z, a generation already accustomed to algorithmic personalization and micro-rewards in digital spaces, these mechanisms create a seamless bridge between psychological desire and economic behavior, transforming collecting into a sustained, self-reinforcing cycle.

Another reason behavioral-economic strategies are so effective on Gen Z is that they align with the generation’s broader relationship to uncertainty, reward, and digital culture. Growing up in an environment shaped by algorithmic feeds, micro-trends, and constant content refresh cycles, Gen Z is already conditioned to respond to intermittent reinforcement, a core principle in behavioral economics that increases the likelihood of repeated engagement. Collecting systems — whether in apps like Pokémon Go, K-pop photocard trading, or limited-run fashion drops — mirror the same mechanics: rewards arrive unpredictably, and the “near miss” feeling of almost completing a set keeps users invested. Social proof, another behavioral-economic principle, magnifies this effect. When influencers, friends, or online communities display sought-after items, the perceived value of these objects rises, and individuals become more willing to take economic risks to avoid the social cost of being “left out.” The combined force of digital visibility, reward uncertainty, and community comparison means that the decision to collect is rarely an individual choice; it is a behavior reinforced by everyone around them that was designed to maximize engagement. As a result, Gen Z’s collecting habits cannot be fully understood without acknowledging how behavioral-economic design intersects with their digital upbringing and value systems.

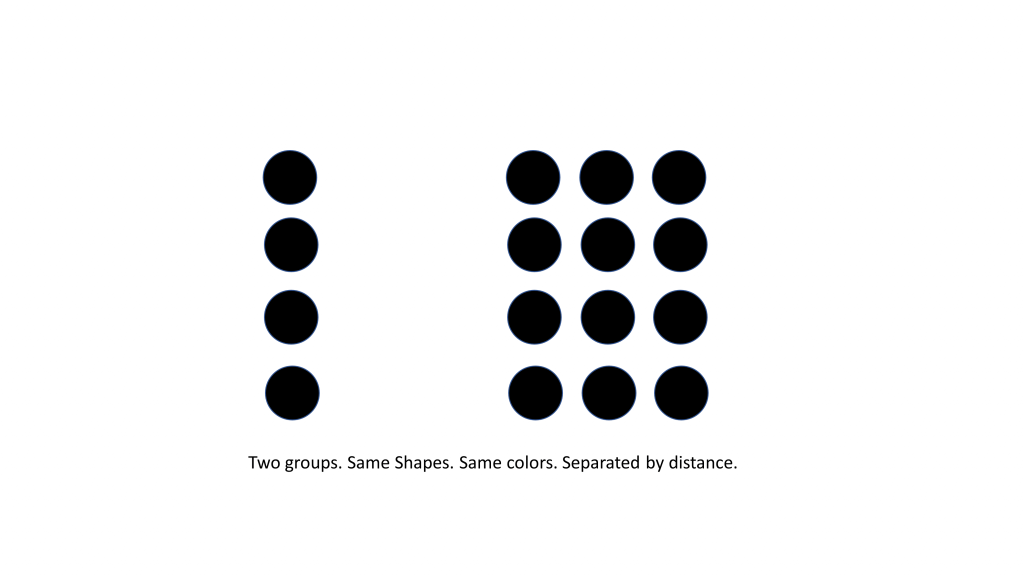

Gestalt principles also play a crucial role in shaping the appeal of collectible items, particularly in how brands design visual systems that emphasize unity, pattern, and completion. In foundational Gestalt theory, the human perceptual system instinctively organizes visual information into meaningful wholes rather than isolated parts — a process driven by principles such as similarity, proximity, and closure. When collectible series use consistent color schemes, repeated character forms, and numbered sequences, they leverage similarity to signal that each piece belongs to a unified whole, making incomplete sets feel visually and emotionally disjointed rather than discrete (Canva Learn). Clusters of items displayed together exploit proximity, leading viewers to perceive grouped objects as belonging together, while closure—our tendency to mentally “fill in missing pieces”—creates internal pressure to complete an unfinished collection (thoughtbot). Even affordances like stackable packaging or interlocking shapes communicate how items relate to one another, further reinforcing the perceptual pull toward collection completion. By tapping into these innate visual tendencies, brands craft collectible ecosystems that feel naturally compelling, making the desire to “finish the set” as much a perceptual instinct as an economic choice.

Beyond basic grouping laws like similarity and proximity, Gestalt theory has a rich empirical foundation showing how perceptual organization deeply influences how consumers interpret and emotionally respond to visual forms. A study looking into Gestalt psychology demonstrates that the human visual system automatically organizes elements into coherent wholes, meaning that figure-ground relationships, continuity, and Prägnanz (simplicity and good form) shape not only what we see but how we interpret object sets as unified and meaningful. These perceptual processes operate rapidly and unconsciously, with grouped items capturing attention more effectively and enhancing memory for those visual patterns (Wagemans et al., 2012). Research from Cambridge University shows that Gestalt principles can predict aesthetic preferences for product form — for example, symmetry, parallelism, and continuity each contribute to how consumers judge the harmony and attractiveness of objects in three-dimensional space (Valencia-Romero et al., 2017). These findings go to show that the very structure of collectible sets — from how items are visually related to one another to how they are presented in space — can enhance their appeal and the psychological satisfaction consumers get from assembling them.

While Gestalt principles explain how visual organization drives the desire to complete collections, multisensory design expands this influence beyond sight, engaging the body and emotions more fully in the collecting experience. Collectibles are rarely experienced as purely visual objects; instead, they are designed to be touched, opened, displayed, and even heard. Research on multisensory design emphasizes that engaging multiple senses simultaneously enhances emotional attachment and perceived value, as sensory cues work together to create richer, more memorable experiences. Texture-heavy packaging, the resistance of sealed blind boxes, the sound of foil wrappers, and the weight of a sneaker box all contribute to anticipation and reward, transforming acquisition into a ritual rather than a transaction. These sensory layers reinforce behavioral-economic mechanisms like anticipation and reward prediction, while also strengthening emotional bonds between consumers and objects. For Gen Z, a generation that values experience as much as ownership, multisensory design helps explain why collecting feels immersive and meaningful — not simply because of what the item is, but because of how it is felt, handled, and experienced in the moment of acquisition.

Multisensory design heightens the appeal of collectible culture by engaging consumers beyond visual perception, transforming acquisition into an embodied and emotionally charged experience. While speaking about a TED Talk by Jinsop Lee, Akna Marquez explains how “many of life’s greatest pleasures (like eating and sex) are enjoyed deeply because of the presence of multiple senses interacting at the same time,” and that effective design intentionally activates multiple sensory channels to create stronger emotional responses (Marquez, 2025). This principle is especially evident in collectible products, where texture, weight, sound, and even resistance play key roles in shaping anticipation and reward. Similarly, research by creating agency Astriata emphasizes that “Beyond engaging solely through visual elements, we can also stimulate the auditory, olfactory, gustatory, and tactile senses to evoke emotion and improve the user experience,” (Astriata, 2024). For Gen Z collectors, the crinkle of packaging, the smooth finish of a photocard, or the ritualistic act of opening a blind box are not incidental details but central components of value creation. These sensory cues heighten emotional investment at the moment of purchase, reinforcing behavioral-economic mechanisms like anticipation and perceived reward while turning collecting into a ritualized experience. In this way, multisensory design bridges perception and emotion, ensuring that collectibles are not only seen as desirable objects but felt as meaningful experiences.

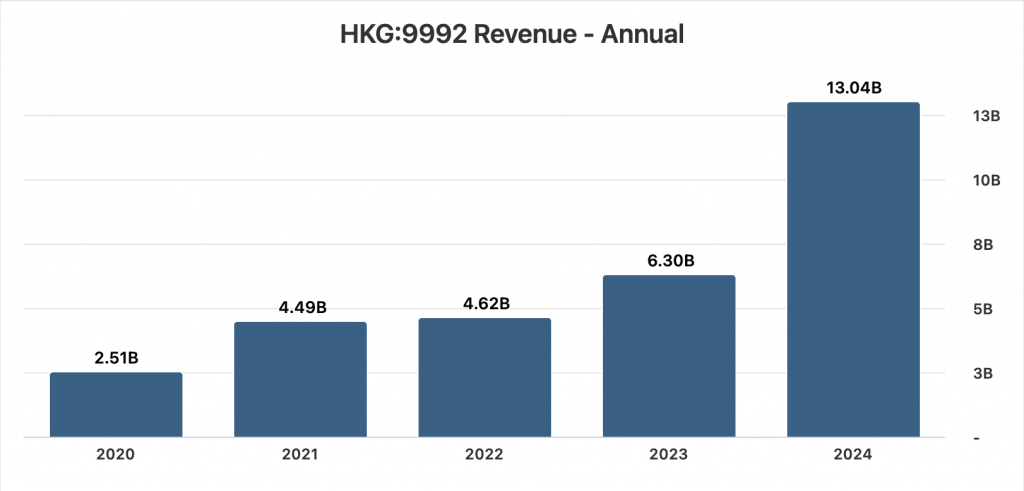

To get specific, Pop Mart’s rise from niche art-toy maker to a global collectible powerhouse illustrates how multisensory design — combined with psychological and cultural strategies — can turn otherwise “useless” objects into deeply engaging experiences. Central to Pop Mart’s appeal is the blind-box format, where customers don’t know which figure is inside until after they open it, turning the act of unboxing into a moment of suspense, tactile engagement, and emotional payoff that drives repeat behavior and social sharing. The brand’s founder captured this feeling, even saying that “if we make dolls useful, our sales are bound to decline…If the dolls have practical attributes, the next time you feel the desire to buy something, you won’t be so impulsive; instead, you’ll think about whether you already have one at home,” suggesting that the emotional and experiential qualities of the unboxing moment are the real product (D, 2025). This aligns with research showing that blind-box products create “special shopping experiences” that appeal particularly to young consumers through uncertainty, surprise, and emotional gratification, key components of multisensory engagement (Lin, 2023). Pop Mart’s use of vibrant character IPs, tactile packaging, and virality around unboxing turns a simple purchase into a multi-sensory event — one that is seen, touched, and performed publicly on platforms like TikTok and Instagram, where unboxing content acts as user-generated marketing (Jeyaretnam, 2025). The result is a consumer experience that feels playful, personal, and socially rewarding — a powerful combination that has helped Pop Mart transform blind boxes into emotional artifacts of Gen Z culture.

Like Pop Mart’s blind-box collectibles, Pokémon cards rely heavily on multisensory and emotional design to sustain long-term engagement, though they operate through a different material and cultural logic. Pokémon cards, around much longer than Labubus, activate sensory experience through the ritual of pack opening: the tactile resistance of foil wrappers, the distinct smell of freshly opened cards, and the practiced hand motions used to reveal rare cards in a specific order all heighten anticipation and emotional payoff. This sensory choreography transforms each pack into a suspenseful moment, mirroring Pop Mart’s emphasis on surprise while grounding it in nostalgia and familiarity. Emotionally, Pokémon cards differ in that they connect present-day collecting to childhood memory, allowing Gen Z collectors to re-engage with a franchise they encountered early in life while reframing it as an adult hobby, investment, or social performance. Visual design further reinforces this attachment: holographic finishes, rarity symbols, and evolving card aesthetics signal value instantly, guiding emotional response before rational evaluation occurs. While Pop Mart leans into novelty and character IP discovery, Pokémon cards thrive on emotional continuity, blending surprise with nostalgia and long-term brand trust. Together, these phenomena show that successful collectible ecosystems do not rely on randomness alone, but on carefully designed sensory rituals that transform opening, revealing, and owning into emotionally resonant experiences.

While multisensory design explains how collectibles feel, affordances and interaction design explain how collectors intuitively know what to do with these objects — how to open them, handle them, trade them, and display them. Affordances refer to the perceived actions an object suggests to a user, shaping behavior without the need for explicit instruction. As the Interaction Design Foundation explains, affordances signal the possible actions users can take with an object based on its appearance, meaning that design subtly guides interaction before conscious thought occurs (Interaction Design Foundation). In collectible culture, affordances are deliberately embedded into packaging and product form: tear tabs invite slow reveals, resealable sleeves encourage preservation, and rigid boxes signal value and permanence. Pokémon card packs, for example, afford careful opening and sorting, while Pop Mart boxes afford shaking, stacking, and display. These interaction cues transform collectibles into objects meant to be handled repeatedly rather than consumed once, reinforcing emotional attachment and prolonged engagement. By designing for intuitive interaction, brands reduce friction while increasing ritual, ensuring that collectors not only desire the item but understand how to engage with it in socially and culturally meaningful ways.

Affordances intersect powerfully with Gestalt principles and visual depth cues to shape how collectors perceive and interact with objects in ways that feel intuitive and meaningful. In design theory, an affordance is understood as a signal that suggests how an object may be used — “a perceived signal or clue that an object may be used to perform a particular action,” whether physical or digital, and it relies on perceptual cues to communicate possibilities to the user (Postolovski, 2014). These perceived action cues are effective when they align with familiar visual organization rules: depth cues like shadows, perspective, and layering create a sense of hierarchy and prominence that helps users see which parts of a product or interface are interactive or important. Depth cues are especially relevant in physical packaging and digital displays alike, where contrast, shading, and perspective build a sense of form that attracts attention and suggests how to engage with an object. At the same time, Gestalt principles — such as proximity and similarity — organize elements into visually meaningful groups, so that related affordances appear unified and easy to understand without conscious thought. For example, affording a pull or push action through design features like raised edges or overlapping layers is more effective when those cues are grouped and visually ordered, reducing cognitive load and creating a seamless interaction experience. Together, affordances, Gestalt organization, and depth cues create a perceptual ecosystem where how an object looks and where it appears in space both guide collectors toward intended sensory and emotional engagements, making collectible interactions feel intuitive, satisfying, and instinctive.

Altogether, behavioral economics, Gestalt perception, multisensory design, and affordances reveal that Gen Z’s collecting habits are less about ownership and more about emotional meaning-making and social positioning. Behavioral economics explains why scarcity, uncertainty, and loss aversion motivate repeated purchases, while Gestalt theory explains how visual systems frame collections as incomplete wholes that demand closure. Multisensory design deepens this pull by turning acquisition into ritual, engaging touch, sound, and anticipation in ways that strengthen memory and emotional attachment. Finally, affordances guide interaction intuitively, teaching collectors how to open, handle, preserve, and display items without explicit instruction. Together, these frameworks show that collecting is not a passive response to trends, but an active, embodied experience shaped by design decisions that prioritize feeling over function. For Gen Z, whose consumption habits are deeply intertwined with digital culture and identity performance, collectibles become tools for self-expression — objects that communicate taste, belonging, and emotional resonance rather than practical utility.

Importantly, these design strategies never act alone. Instead, they are amplified by platforms where visibility, community, and performance matter. As explored in discussions of multisensory experience and interaction design, emotionally resonant objects gain value when they are shared, displayed, and validated by others. A newer synthesis in UX and emotional design research argues that products succeed when they support more meaningful experiences that align with users’ values and identities rather than purely functional outcomes — a framework that maps closely onto Gen Z’s relationship with collectibles (Interaction Design Foundation). Collecting, then, becomes a social language: Pop Mart figures on a shelf, Pokémon cards in protective sleeves, or photocards arranged in binders all signal care, intention, and cultural literacy. By designing for perception, sensation, and interaction simultaneously, brands transform collectibles into emotional artifacts — objects that feel personal, communal, and worth protecting. Ultimately, Gen Z’s obsession with collecting is not irrational; it is the logical outcome of design systems that skillfully align psychology, perception, and emotion with the social desire to belong and be seen.

This paper has explored Gen Z’s obsession with collecting not as a fleeting trend, but as a carefully constructed interaction between psychology, design, and emotion. Through the lenses of behavioral economics, Gestalt perception, multisensory design, and affordances, collecting emerges as an experience engineered to feel intuitive, rewarding, and socially meaningful. Scarcity and uncertainty activate emotional decision-making; Gestalt principles frame collections as incomplete wholes that invite completion; multisensory cues transform purchasing into ritual; and affordances guide interaction in ways that feel natural rather than imposed. Together, these strategies reveal that contemporary collectibles are not valued for utility, but for the emotional, sensory, and social narratives they enable. For Gen Z, collecting becomes a way to externalize identity, participate in community, and create moments of control and pleasure within an otherwise unstable economic and digital landscape.

Ultimately, the success of collectible culture underscores a broader shift in design priorities: from function to feeling, from ownership to experience, and from products to stories. As Ellen Lupton says in Design Is Storytelling, “design

embodies values and illustrates ideas. It delights, surprises, and urges us to action,” (Lupton, 2017). Collectibles exemplify this shift perfectly — each blind box, card pack, or display shelf tells a story shaped by anticipation, discovery, and belonging. Understanding Gen Z’s collecting practices, then, is not simply about consumer behavior; it is about recognizing how design leverages perception, sensation, and emotion to create meaning in a culture where experience is often more valuable than possession.

References

Module Readings (all from Module 4)

Astriata. (2024, October 17). How multi-sensory web design can improve the user experience. Astriata. https://astriata.com/how-multi-sensory-web-design-improves-user-experience/

Bonner, C. (2019, March 23). Using gestalt principles for natural interactions. thoughtbot. https://thoughtbot.com/blog/gestalt-principles

Bridgeable. (2024, February 7). The top 5 behavioural economics principles for designers. Bridgeable. https://www.bridgeable.com/ideas/the-top-5-behavioural-economics-principles-for-designers/

Canva. (n.d.). Simplicity, symmetry and more: Gestalt theory and the design principles it gave birth to. Canva. https://www.canva.com/learn/gestalt-theory/

IxDF – Interaction Design Foundation. (2016, September 13). What are affordances?. IxDF – Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/affordances

Lupton, E. (2017). Design is storytelling. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Marquez, A. (2025, August 4). Introduction to multi-sensory design. Akna Marquez. https://www.aknamarquez.com/blog/2017/7/23/what-is-multi-sensory-design

Peer-Reviewed Journals

Cao, C. C., Brucks, M., & Reimann, M. (2025). Seeking Structure in Collections: Desire for Control Motivates Engagement in Collecting. Journal of Consumer Research, 52(3), 480–501. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucae071

Lin, Z. (2023). Exploring Pop Mart Marketing Mechanics and Related Effects. Highlights in Business, Economics and Management, 7, 415-420. https://doi.org/10.54097/hbem.v7i.7004

Wagemans, J., Elder, J. H., Kubovy, M., Palmer, S. E., Peterson, M. A., Singh, M., & von der Heydt, R. (2012). A century of Gestalt psychology in visual perception: I. Perceptual grouping and figure-ground organization. Psychological bulletin, 138(6), 1172–1217. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029333

Valencia-Romero A., Lugo J.E. (2017) An immersive virtual discrete choice experiment for elicitation of product aesthetics using Gestalt principles. Design Science. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318657873_An_immersive_virtual_discrete_choice_experiment_for_elicitation_of_product_aesthetics_using_Gestalt_principles

Internet Articles

D, E. (2025, March 19). Pop Mart’s toy empire: How ‘useless’ collectibles became a social media sensation | by Explorer D | Digital Society | Medium. Medium. https://medium.com/digital-society/pop-marts-toy-empire-how-useless-collectibles-became-a-social-media-sensation-1d5ce24bb39f

Jeyaretnam, M. (2025, March 26). Inside pop mart’s Global Toy Takeover. Time. https://time.com/7271656/popmart-china-blindbox-labubu-designer-toys-genz-luxury-industry-revenue/

Komninos, A. (2025, September 25). Norman’s three levels of design. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/norman-s-three-levels-of-design?srsltid=AfmBOoorgEVSbzFb1IrgQg_FhWMVr-fiu3bPae3T_ybVwj-EtPBqPTiV

Postolovski, N. (2014, June 24). What is the most underrated word in web design?. Smashing Magazine. https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2014/06/affordance-most-underrated-word-in-web-design/