Adopting a pet is much more than a transaction — it’s an emotional journey. What if we treated that journey with the same empathy and design thinking used in UX? A customer (or user) journey map helps us narrate someone’s path, see their motivations, frustrations, and “aha” moments.

What are Journey Maps?!

A journey map, defined by UX Mastery, is “a visual interpretation of the overall story from an individual’s perspective” over time and across channels. They can help us shift from a general view to an outside-in perspective, seeing each touchpoint as the adopter experiences it.

To further note the significance of journey maps, Paul Boag of Smashing Magazine wrote:

“Data often fails to communicate the frustrations and experiences of customers. A story can do that, and one of the best storytelling tools in business is the customer journey map.”

A well-designed map illuminates hidden pain, emotional peaks and valleys, and opportunities for improvement.

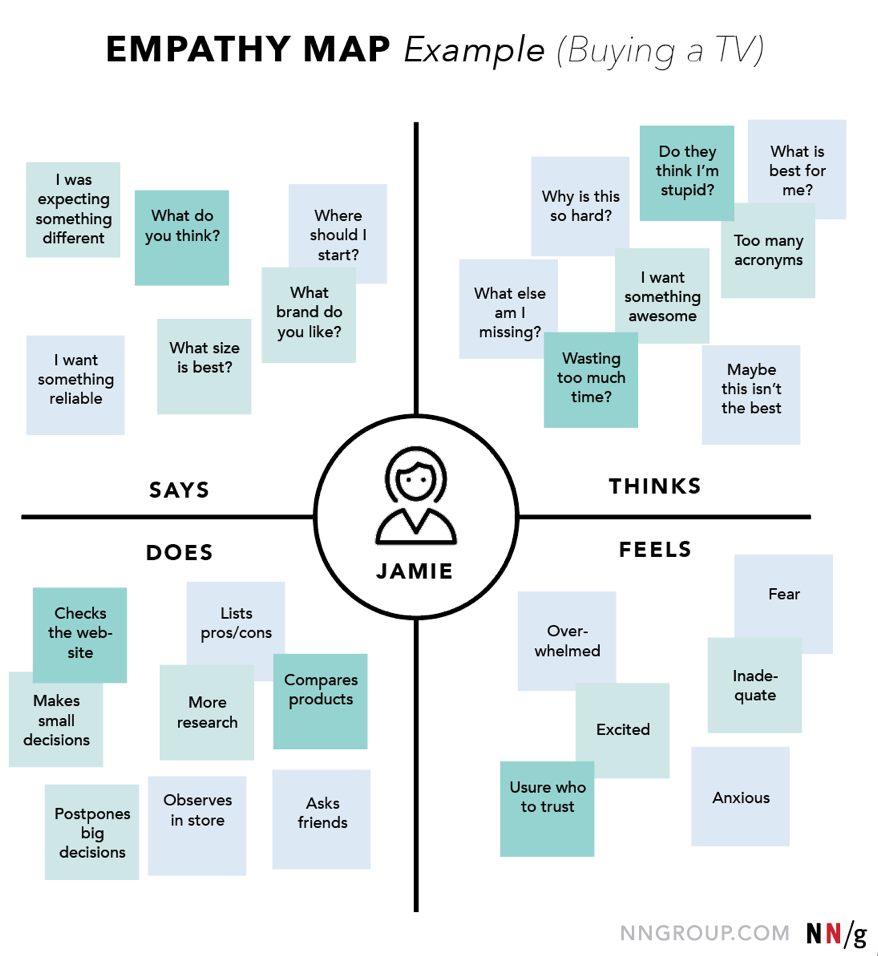

A UX Mastery article outlines the key components of journey maps:

- Personas

- Timelines (phases)

- Emotions (peaks/valleys of the experience)

- Touchpoints (what the person is doing)

- Channels (where it happens)

Using those must-haves, I created a journey for Briana, a 23-year-old content creator living in a new city, who has been thinking about adopting a new furry roommate.

To get more specific, Briana also has some rules regarding her new furever friend. The dog must:

- Stay small (to be able to stay in her building),

- Match her energy (active, lively, and energetic),

- Is ultra-friendly and camera-comfortable.

Smaller details, like lease rules (weight or breed restrictions), occasional long filming days, and a moderate budget were also considered 🙂

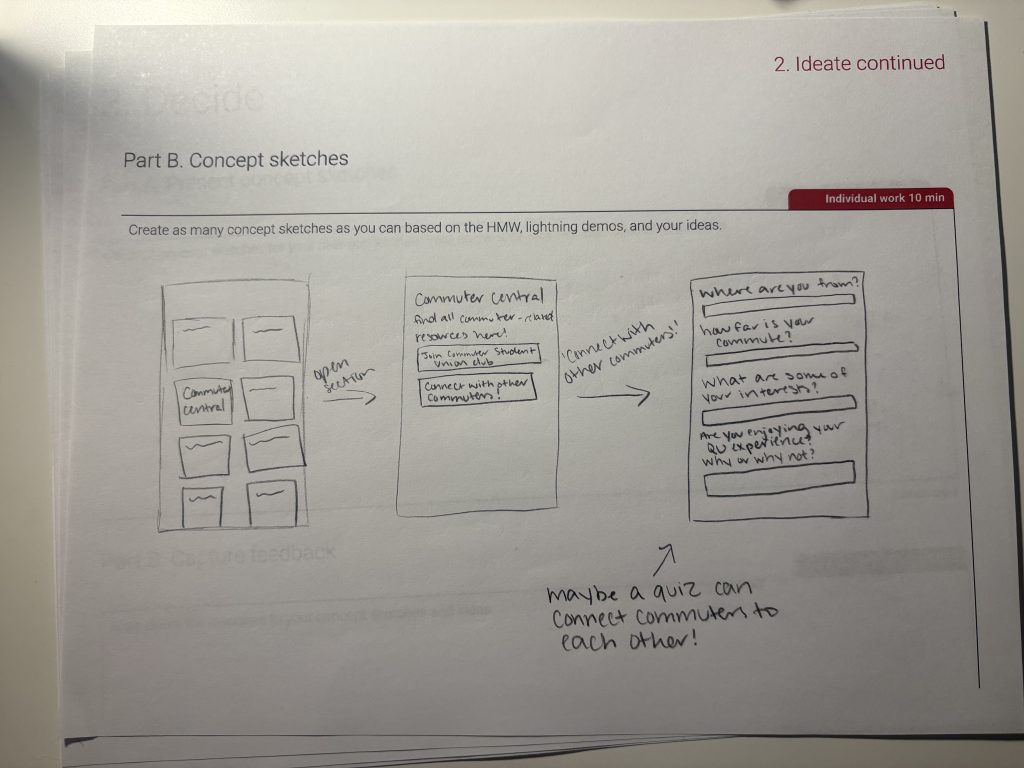

With all of this in mind, I sketched a detailed journey to see what she needs at each step.

1. Awareness

At first, Briana scrolls through TikTok and Instagram reels about “small active dog breeds,” reads breed comparison posts, and stumbles on rescue profiles. She begins Googling: “active small dog apartment friendly,” “adopt small breed near me”. Here, her emotion is excited mixed with nervousness about her new journey ahead.

Opportunity: content creators or shelters should publish short listicle content (“Top 5 active small breeds”) or reels that show real apartment dogs in action.

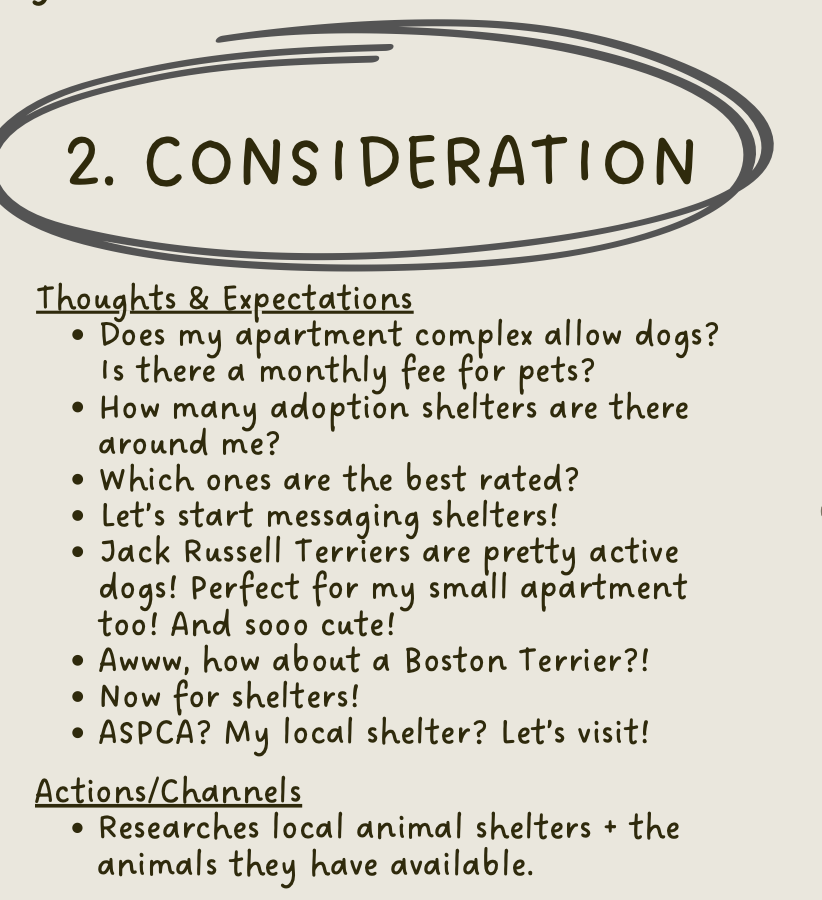

2. Consideration & Research

Here, Briana looks into her apartment rules, local shelter websites, and DMs shelters to ask specific questions about energy, socialization, and separation tolerance. She bookmarks promising profiles.

Frustration arises when the listings are vague: “good with people” without nuance, no video showing behavior. A rich video snippet or temperament tag can help remove this uneasiness!

3. Visiting

Once she narrows it down, Briana visits shelters and meets fostered dogs. She tests how the dog reacts when she walks away, how it handles a phone (camera), and whether it’s comfortable meeting strangers and other dogs.

This is a “moment of truth” — a point of high emotional impact. According to UX mapping principles, these moments are prime for leaving a lasting positive impression for the customer.

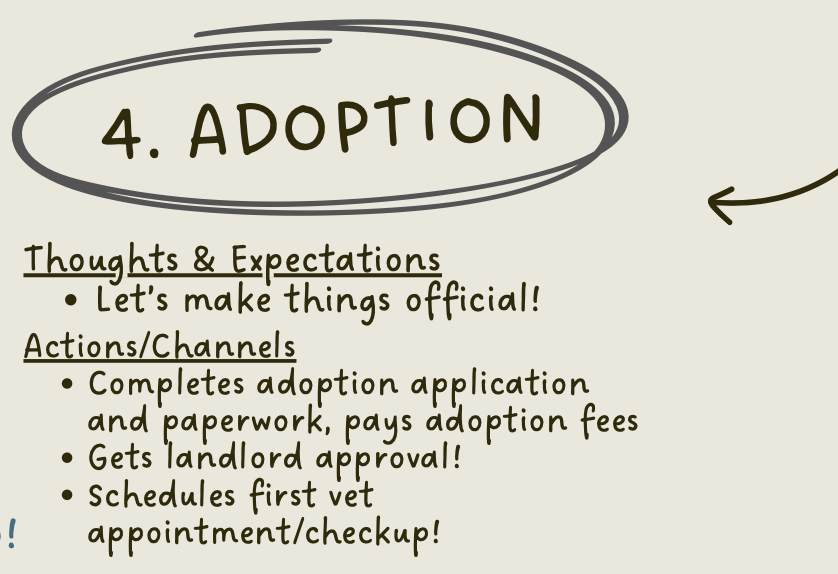

4. Adoption/Paperwork

Briana has found a furever friend! Ash, a two-year-old Boston Terrier, loves hikes and was the most energetic pup in his litter. Briana can’t wait to spend the rest of their lives together.

This stage, however, often involves anxiety over landlord approvals, adoption fees, and transport logistics. Her heart is in it, but delays or surprise requirements can cause hesitation in this part of the process.

To smooth this, shelters should offer adoption toolkits (landlord letter templates, starter equipment suggestions, local trainer contacts) to reduce overwhelming moments like this for adopters.

5. Onboarding (First 30 Days)

This phase is about habits: the first vet visit, crate training, walks, socialization, and linking dog life to her content routine (e.g. shooting “meet my dog” reels). She experiments with leaving the dog alone for short stretches, sets up enrichment toys, and teaches leash manners.

This is where consistency is crucial. Small missteps in training or routines often lead to stress or regression, which can be stressful for new pet owners. Offering a one-stop shop for newly adopted animals to receive training can definitely help ease this issue!

6. Advocacy

If things go well, Briana becomes an ambassador. She shares her adoption story, tags the shelter, posts updates, and may inspire others to adopt. Her journey becomes content — which also feeds the adoption ecosystem! Thanks, Briana!

Insights & Opportunities

Overall, creating this customer journey map allowed me to better visualize a quite emotional journey for a customer. In this process, I began to understand that:

- Videos are gold! At every stage, from research to meeting the pup, short video content beats static photos for conveying temperament.

- Micro-moments matter: The moment she tests camera comfort or a short separation is where she’ll decide yes or no.

- We can reduce friction or hesitation by using simple tools (landlord letter, adoption kit) to reduce drop-off after adoption.

- The first 30 days can be fragile! Quietly supporting or having training check-ins can improve retention and satisfaction for customers.

- Content synergy: Because Briana is a creator, the adoption process can feed into her content pipeline. This can be both good for her and good for the shelter’s visibility!

Final Thoughts

Journey maps aren’t just for tech or big companies — they’re frameworks for empathy. By translating Briana’s adoption journey into stages, emotions, and touchpoints, you can reveal where help is needed and where relationships may deepen. As UX Mastery puts it, “the process of journey mapping is what’s most important” — not just the visual artifact. And as Smashing Magazine reminds us, data alone fails to capture the lived experience — but stories have the opportunity to bridge that gap.

I would highly recommend the practice of customer journey mapping for anyone with newer ideas or projects. This way, you can better understand both your customers and your product.